Conservationists and salmon fishermen are united in their concerns about the dwindling number of Atlantic salmon now residing in rivers across the UK. Pollution, predation even climate change are thought to be potential causes of a massive 70 per cent decline in recent years. But in truth no-one really knows why salmon stocks are disappearing.

However, remarkable new research being carried out in a state-of-the-art natural river laboratory on the River Frome in Dorset by the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust could shed light on some of the critical factors affecting our Atlantic salmon stocks in rivers across the country.

With more than 40,000 young salmon now tagged with Passive Integrated Transmitters (PIT tags), these fish, many of which will migrate to the sea in the spring, will enable the researchers to build an accurate picture of how the river environment is affecting the success of salmon at sea. For example it will help to clarify whether their size when leaving the river affects their survival and the length of time they spend at sea.

Dr Anton Ibbotson, who runs the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust’s Salmon and Trout Research Centre at East Stoke, in Dorset, explains the latest findings of this long-standing research, “This autumn was the fourth year that we have tagged more than 10,000 salmon parr. In total 40,000 fish have been tagged over this period and we are monitoring their progress closely as they leave the river and significantly, if and when they return from the sea in two or three years time.”

Already this important research is identifying some of the key issues that relate to the migration of juvenile salmon. Dr Ibbotson said, “A few years ago we discovered a significant downstream migration of salmon parr from the streams where they were born down to the tidal reaches of the River Frome in late October.

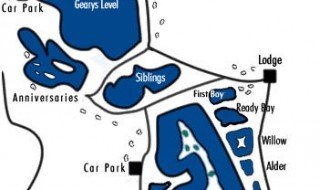

“This raises the question of why so many parr migrate away from safe areas to sites that contain many predators such as bass, sea trout and pike. Our monitoring suggests that some sites produce more autumn migrants than others, which could imply that it is the physical attributes of the sites themselves, such as the amount of over-winter cover or an excessive number of fish within individual sites that causes excess fish to migrate out of these relatively safe areas.”

This autumn, researchers tagged fish on approximately 100 sites in order to measure specific aspects such as depth, water velocity and cover. They also recorded the number of predators such as eels and pike. Further research over the next few years will also involve manipulating some of the sites to see whether it is possible to increase or decrease the number of autumn parr that migrate from these sites by increasing the amount of cover as winter approaches.

“Over the next few years, we hope to unlock some of these mysteries in order to identify some of the general problems that are going wrong in our rivers so that we can make recommendations to river managers across the country to improve the situation,” explains Anton Ibbotson.

He continues, “This is a unique opportunity to understand the survival of fish in the freshwater environment and will give us better insight into their levels of survival. When the fish return previous tagging will indicate precisely what age they are and which catchment they have come from and whether they are doing well or badly. If we mark so many fish in a tributary and none come back, we would be worried as this could indicate a problem in the river.

The adult salmon counter detects the adults as they return to spawn. This adult salmon is 1.03 metres long!