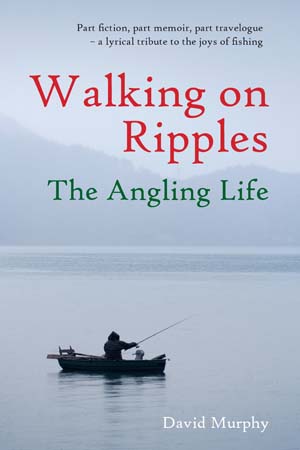

David Murphy began writing “Walking on Ripples” by compiling an article on fish caught abroad – in Spain, Portugal, the Canaries and further afield in Florida and Mauritius. He enjoyed writing this so much he decided to write about angling in his favourite Irish location: Donegal. This last segment led seamlessly into short fiction, based on fishing a Donegal lough, which won the Maurice Walsh Award for short stories. He realised he had written over ten thousand words – a quarter of a book! – so he kept on writing. Five of the eleven chapters in “Walking on Ripples” are totally invented, but based on fishing or other water-related subjects. The other six are factual and true: and about angling. There’s a lot about fishing in Waterford where he has a holiday home, and Cork (where he’s from). All chapters are linked thematically; dealing with the art of fishing. It’s an unusual approach that has rarely been attempted before. It’s a very Irish book yet has appeal broader than that. General readers will enjoy it because this is not a dry fishing manual brimming with technical jargon. It’s a lyrical approach imbued with a great sense of place – an evocative (and sometimes dark) sideways look at the world down the length of a fishing rod, with a frequent touch of humour thrown in. An ideal stocking filler: a charming, very attractive, and highly unusual book popular with readers of fiction and fans of fishing – and what family does not know at least one angler?

Here’s a snippet from the back cover:

“Some fishermen thrive on numbers. Good luck to them. That’s what floats their boat. Give me an hour, or two or even three, with nothing. Then one little fish to save the day. Give this to me any time, more fun than the relentless reeling in of bucket loads of suicidal fish. Grant me time to take a break from casting, to sit on flat rocks and contemplate the land, the water, the birds that fly and cartwheel in overhead sky. Watch gulls and other birds dive – now they know how to fish. Allow my eyes time to examine what floats as flotsam in the ripples at my feet. Let me jettison the jetsam of my life, and get on with taking in the great world that surrounds. The inhaling of things that matter, like smell of salt spray; tang of it in my nostrils of a windy day when I stand thirty feet up to be truly safe from breakers smashing into the rocks beneath, a day when my eyes witnessed but refused to believe what happened next.”