Salmon populations may be adversely affected by climate change because of changes in their river habitat – unless action is taken to help river ecosystems adapt to unavoidable climate change, according to findings released today.

The Environment Agency study, based on detailed climate modelling in three example catchments, found that salmon in the upper River Wharfe in Yorkshire may be forced to find new homes by the 2050s because of increased temperatures and less rainfall.

Salmon rely on rivers providing different water depths and river speeds at various stages in their life cycle. Less rainfall due to climate change could reduce river flows, making it harder for salmon to move between breeding grounds.

However, action could be taken in some locations to reduce salmon vulnerability by prioritising the restoration of river habitats, especially upland headwaters, and also to remove barriers to provide free movement of fish. Tree planting along riverbanks to increase river shading to reduce potential water temperature increases, as well as tighter controls on water abstraction, could also help river ecosystems adapt better to climate change.

Speaking today at a conference on Climate Change and the UK’s Aquatic Ecosystems in London, Environment Agency Research Fellow Harriet Orr said the project had put the long-term management of freshwater ecosystems under the microscope.

“While we can limit the worst effects of climate change by reducing emissions, we need to start thinking about how we adapt our river management practices for unavoidable climate change. Our rivers, and the fish within them, are particularly vulnerable and we need to start planning for that now,” Dr Orr said.

“The Environment Agency, with others, has worked hard to improve the River Wharfe’s health so that salmon are returning in increasing numbers. This river provides a good indicator of how salmon populations could be affected if upland streams and rivers in this region become drier. With less water flowing, salmon will have fewer suitable habitats for breeding, finding it harder to access these sites. Young fish will also find it difficult to move to suitable feeding areas as they develop.

“But this also has serious implications for salmon rivers in southern England, especially in the drought-prone south east were the impacts of climate change could be even more serious.”

Dr Orr said changes in water temperature could also be critical to freshwater ecosystems.

“Most of the species and communities in rivers have a limited range of temperature tolerance. An increase of 2-3 degrees Celsius in temperature, along with changes in flow, could see some species, such as larval insects like stoneflies or mayflies, change distribution, decline in population or even become extinct by the 2080s.

“The diversity of insects in a river has often been used as an indicator of overall ecosystem health because they are critical in the food chain. A reduction in their abundance could have a serious knock-on effect for species such as fish, which rely on these insects as a food source.

“The study also looked at brown trout populations, whose breeding grounds are not as sensitive to climate change impacts. But even these fish could be forced further downstream in some Yorkshire rivers because of the predicted drop in water depth and flow.

“Although this is a limited study on one river, it highlights the urgent need for more collaborative research, with improved monitoring and better understanding of climate change impacts at both local, regional and national levels. This is going to be essential if we are to build up an accurate picture of what’s happening, and how all of us involved in looking after rivers should change our approach to manage for unavoidable climate change,” Dr Orr said.

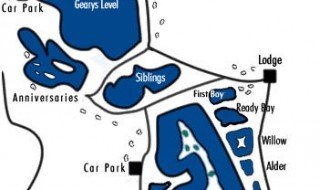

Preparing for Climate Change Impacts on Freshwater Ecosystems (PRINCE) focussed on the potential impact on insect life on three sites already known to be vulnerable to climate change impacts: the upper River Wharfe in Yorkshire, the middle reaches of some Yorkshire rivers, and the headwaters of the Afon Tywi in mid Wales. The assessment used predicted future river flows and temperatures, field survey data and simulation models. Although very difficult to predict the future, the results indicate what could happen under two possible future scenarios.

The study, also funded by the Countryside Council for Wales and Natural England, will be used to provide guidance to UK agencies on the likely future impacts for the management of freshwater ecosystems. It is available at www.environment-agency.gov.uk