One of the most dependable patterns ever created? The Black Pennell will tempt double-figure sea trout as well as it will buzzer-feeding rainbows.

THE first fly I learned to tie, thirty years ago, was the Black Pennell, writes Andy Petherick.

The tying method was illustrated in photo sequences (then an advanced idea) in a little book by Alan Vare, who was manager of Hardy’s shop in the centre of London. I remember buying the book and the excitement that followed when the first simple fly was completed.

A still greater thrill lay ahead when my fly rose and hooked a trout on a Scottish loch. I had done it and it worked! This was the prelude to years of pleasure and interest that I have had from tying flies.

The Black Pennell that I chose to start with all those years ago was a random choice, but it is one fly that I would now never be without. The name comes from one of the pundits of the late Victorian period, Mr H. Cholmondley Pennell, who was an author of fishing books and editor of The Field magazine.

In those days there were continual disputes between angling authorities about everything, and Mr Pennell was a scrapper who liked to mix it with anybody whose opinions differed from his own.

There can be no dispute though about the effectiveness of the fly which perpetuates his name: the Black Pennell is the loch fisher’s sheet anchor, and also a winning sea trout fly in larger sizes. The black fly is of course very much older than Mr Pennell.

Anglers have been casting black palmered trout flies for centuries. The first published description of a black fly comes in the Treatise of Fishing with an Angle in the year 1496.

Every fishing guide published since made mention of black flies, right down the ages. So old Mr Pennell had a solid basis of history behind him. But if he was not truly original in his creation, Mr Pennell deserves the gratitude of posterity for two tiny details which he incorporated and which make his black fly special: first, he insisted on a thin meagre body of black floss.

Often the flies you find for sale today have tubby bodies tapered from the shoulder. These should be rejected. A really sparse uniformly thin body is the right recipe.

Second, Mr Pennell tied his fly with what professional tyers call ‘kick’, that is, with the finishing knot behind the hackle rather than in front. This ploy forces the hackle fibres to stand out and to remain at a 90 degree angle to the hook shank, giving life and movement to the fly.

Dressing

Hook: Any traditional wet fly pattern size to suit application

Silk: Black

Tail: Golden pheasant tippet

Body: Black floss

Rib: Silver wire

Hackle: Soft black hen

|

| 1. Take the silk along the shank in close-touching turns. Stop at the point just above the barb of the hook. |

|

|

| 2. Tie in a tail of golden pheasant tippet, secure this along the entire length of the shank, stop at the eye end of the hook. |

|

|

| 3. Tie in a length of silver wire and return the silk in close turns to the start point near the bend of the hook. |

|

|

| 4. Tie in a length of black floss and return the silk in close wraps to the front of the fly. This process makes for an even body. |

|

|

| 5. Form the body with overlapping wraps of the floss. If necessary, go back down the shank and then back up to get a good coverage. |

|

|

| 6. Tie the floss in at this point and form the rib with the silver wire. Make sure that you achieve nice, neat, even spacing. |

|

|

| 7. Tie the wire in at the head of the fly. Ensure that you do not create any unnecessary build-up at the head. |

|

|

| 8. Select a hackle of the correct length and tie this in with the concave side of the feather parallel to the shank. |

|

|

| 9. Keeping the silk behind the hackle, form the hackle with three touching wraps around the shank. |

|

|

| 10. Making sure that you do not trap any fibers, zigzag the silk through the hackle – this increases the durability. |

|

|

| 11. Tie the hackle off and form a neat head. Try and keep it as small as possible with the minimum number of turns of silk. |

|

|

| 12. Finish the fly with a few half-hitches. Apply some clear or black varnish and allow it to dry |

|

|

Variations

The Peacock Pennell

The Pearly Pennell

The Tandem Pennell

The Red Pennell

Stillwater

The Black Pennell really comes into its own on stillwaters fished as a buzzer imitation. Always make sure that you have this fly in small sizes, down to 18 if your eyes can handle it. Fish it on a floating or midge tip line with a painfully slow retrieve when the fish are feeding on buzzers. If you retrieve your cast fly line in less than 10 minutes; you are fishing it too quickly. A slow approach is what is needed to produce consistent results. If takes dry up it is worth trying a Peacock Pennell. The sheen found in the peacock herl is often enough to trigger a response.

River

Designed as a sea trout fly, it is little surprise that this fly is found in most dedicated sea trout anglers’ fly boxes. In smaller sizes this fly is a good bet in low-water conditions. It is best to use a floating line with a long leader in these conditions. After rain, larger sizes of the fly come into play. A tandem fished on a sunken line will produce fish from seemingly fishless pools. It is important to get the black hackle as soft as possible so that the fibres really work in the current to tempt the fish into taking.

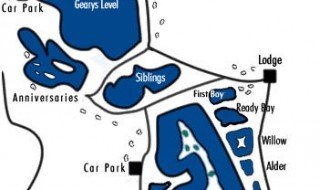

Loch

On the Scottish lochs this is a favourite for both brown and sea trout. The dressing varies slightly north of the border; they like to oversize the hackle and the result is lots of movement.

There is a lot of debate as to the best place to fish it in a team. Many like it as a middle dropper, some prefer it as a point fly. In cloudy conditions the Red Pennell will often outfish the black version. The addition of a muddler head will provide you with a very effective bob or top dropper. For maximum effect, it is worth palmering the hackle along the entire length of the shank. This will increase the wake and enthuse a better response from the fish.